No products in the cart.

The following is just an introduction to an advanced forensics course focusing on photographic evidence. If you want to learn more and get practical, useful skills in photographic evidence analysis, check it out here >>

On the Origin and History of Photographic Evidence

and Photographic Evidence Tampering

That which we drink in at our ears, doth not so piercingly enter,

as that which the mind doth conceive by sight.

— Richard Hooker

Roman playwright Plautus once wrote, “One eyewitness weighs more than ten hearsays – seeing is believing, all the world over.” Seeing is indeed believing, and this applies not only to the first–hand assimilation of real–world events but to the second–hand ingestion of these events through their pictorial representations as well. And amongst the various kinds of pictorial representations we have devised over the years, photographs are undeniably the most influential.

Photographs are amongst the most accurate methods of documenting people and objects, and the visual information they provide acts as a permanent, unbiased, and universal record of occurrence of events. Given its truth–bearing capacity, this information is often used as evidence for making extremely consequential decisions and judgments in several highly sensitive areas such as journalism, politics, civil litigations, criminal trials, defense planning, and surveillance and intelligence operations. In fact, the forensic applications of photographs were recognized almost as soon as photography itself was invented.

Forensic Applications of Photographs: Origin and History

After the invention of heliography and the creation of the world’s first permanent photographic image or, more specifically, the earliest known surviving photograph in 1826-1827 by French inventor Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, several attempts were made to commercialize photography, but it wasn’t until the invention of daguerreotype cameras by French artist and photographer Louis–Jaques–Mandé Daguerre, that camera manufacturing became an industrial procedure. When these cameras became available to the general public in 1839, photography’s potential for identification and documentation of the criminal classes was recognized, making photographs a widely acceptable forensic means of identification.

The earliest evidence of photographic documentation of prisoners dates back to 1843 in Belgium. By 1848, police in Liverpool and Birmingham, UK, were photographing criminals, and by the mid–1850s, English and French authorities had begun encouraging their law enforcement agencies to photograph prisoners, mostly to prevent escapes and document recidivism.

In 1853, an American photographic journal reported that in France, lawyers were using daguerreotypes as a more eloquent means of convincing the juries and judges of the situation at hand. The journal also described an incident in which the victim's lawyer had used pictures taken on the scene of an accident, which from their seeming realism “explained the whole affair more lucidly than all the oratory of a Cicero or a Demosthenes."

Until the early 1850s, the daguerreotype was the dominant photographic process. Daguerreotypes were produced directly onto silver–coated copper plates, and since they were not made from negatives, they were unique images; the only way to reproduce a daguerreotype was to take a daguerreotype of it. While daguerreotypy generated images of great precision, daguerreotypes could only be viewed straight–on. From an oblique angle, the surface was reflective. Moreover, daguerreotypes were quite expensive, especially those in larger sizes.

The concept of photographic evidence began taking greater strides after a new photographic process, called the ‘collodion process’ or the ‘collodion wet plate process’ was invented in 1851, almost simultaneously by Englishman Frederick Scott Archer and French photographer Jean–Baptiste Gustave Le Gray (although Gray’s work was described as being "theoretical at best"). The collodion process produced a negative image on glass, and was an improvement over the calotype process (introduced by William Henry Fox Talbot in 1841), which relied on paper negatives, and the daguerreotype, which produced a non–replicable one–of–a–kind positive image. The collodion process therefore combined the desirable qualities of the calotype process (i.e., enabling the photographer to make a theoretically unlimited number of prints from a single negative) and the daguerreotype (i.e., enabling creation of images with the sharpness and clarity that could not be achieved with paper negatives).

By the late 1850s, collodion process was in regular use, which coincided with the earliest uses of photographs as evidence, especially in American courtrooms [1]. Over the next two decades, photographs were used in a variety of legal contexts, like land dispute cases, road accidents, civil cases pertaining to signature forgeries, and even a case where enlargements of blood corpuscles were used in an effort to distinguish human blood from animal blood. By the 1870s, photographs were frequently used in criminal cases to prove identity, either of the victim or of the defendant.

Until the 1880s, the art of photography faced several challenges. For instance, the pictures had to be developed immediately upon exposure; if the collodion dried before development, the image would be ruined. Producing a photograph also required a high degree of skill. Taking outdoor pictures required substantial advance preparation; photographers literally had to carry their darkroom with them to the site and set it up prior to exposing the plate. But this all changed with the advent of the gelatin dry plates, which could be bought pre–made. The dry plate process was invented by Dr. Richard L. Maddox in 1871, and by 1879, George Eastman had opened the Eastman Film and Dry Plate Company, where photographers could send their plates to be developed, printed, or enlarged. Photography, therefore, came to require far less skill, which gave rise to amateur photography, and subsequently, the possibility of taking pictures of people without their knowledge. Naturally, reports of people "caught in the act" by the camera began to rise as incriminating photographs made their way into the courtroom [2, 3].

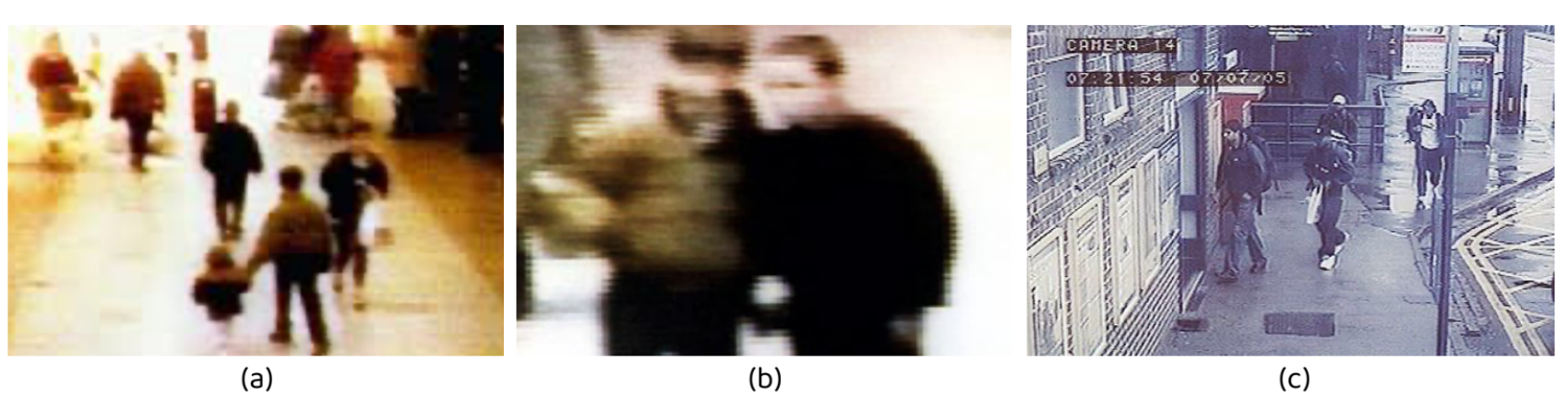

By the end of the 19th century, photographs had become commonplace in the courtroom, and although judges at that time had declared that this form of evidence could only be used for illustrative purposes and not as independent proof, this view has long been abandoned. Figure 1 illustrates some well-known images that either led to successful apprehension and conviction of culprits or effectively galvanized political action and advocacy concerning important social issues by playing an important role in raising public consciousness and a ‘call to arms’.

Figure 1 (a, b) One of the earliest instances of use of visual content as evidence that led to successful conviction of two ten-year-old boys, Robert Thompson and Jon Venables (as seen in (b)) who kidnapped, tortured and murdered two-year-old James Patrick Bulger in Bootle, England, on February 12, 1993. (a) shows Bulger being abducted by Thompson (above Bulger) and Venables (holding Bulger’s hand) out of the New Strand Shopping Centre in Bootle, where he had been shopping with his mother. (c) The four bombers responsible for the July 7, 2005 London bombings captured on CCTV at Luton station and King’s Cross Station on the morning of the attacks. After the bombings, the police examined about 2,500 items of photographs, CCTV footage, and forensic evidence from the scenes of the attacks and further investigations led to several other arrests and convictions for various charges ranging from commissioning, preparing, or instigating acts of terrorism and using threatening words to incite racial hatred, to soliciting the murder of Jews, Americans, and Hindus in London. (d) Ajmal Kasab, the only surviving attacker out of the ten members of Lashkar-e-Taiba Islamic militant organization, who in November 2008, carried out a coordinated series of bombing and shooting attacks across Mumbai, India, that lasted four days. In the image, Kasab can be seen at Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus holding an AK-47 in his hand. Kasab was found guilty of 80 offenses and was sentenced to death. (e) Chechen-American brothers Dzhokhar Tsarnaev and Tamerlan Tsarnaev, the perpetrators of the April 15, 2013 Boston Marathon Bombings in the US. Tamerlan died shortly after midnight on April 19, after he was run over by his brother in a stolen SUV during a police shootout in Watertown, Massachusetts, while Dzhokhar was later arrested and sentenced to death. (f) The killing of Eric Garner by New York City Police Department officer Daniel Pantaleo on July 17, 2014. The officer, who put Garner in a prohibited chokehold while arresting him, was not indicted, which stirred nationwide public protests and rallies, and sparked renewed flames into the Black Lives Matter movement. (g) Three of the five suicide bombers responsible for coordinating the March 22, 2016 Brussels bombings. Three coordinated suicide bombings occurred in Belgium on that day: two at Brussels Airport in Zaventem, and one at Maalbeek metro station in central Brussels. The two surviving attackers were later apprehended. (h) Salman Abedi, making his way to the Manchester arena on May 22, 2017, where he detonated his homemade bomb. Abedi’s identification led to the capture of his brother Hashem Abedi, who was accused of helping his brother plan the attack. (i) The killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin on May 25, 2020. Chauvin handcuffed Floyd and knelt on his neck for several minutes while Floyd pleaded with the four officers present at the scene and repeatedly told them that he could not breathe. The incident resulted in massive public outcry and Black Lives Matter protests worldwide. All four officers involved were fired; Chauvin was charged and later convicted of second-degree unintentional murder, third-degree murder, and second-degree manslaughter, while the other three officers were charged with aiding and abetting second-degree murder and manslaughter. [Pictures Courtesy of BBC News, CNN, Indian Express, Twitter, Wikimedia Commons.]

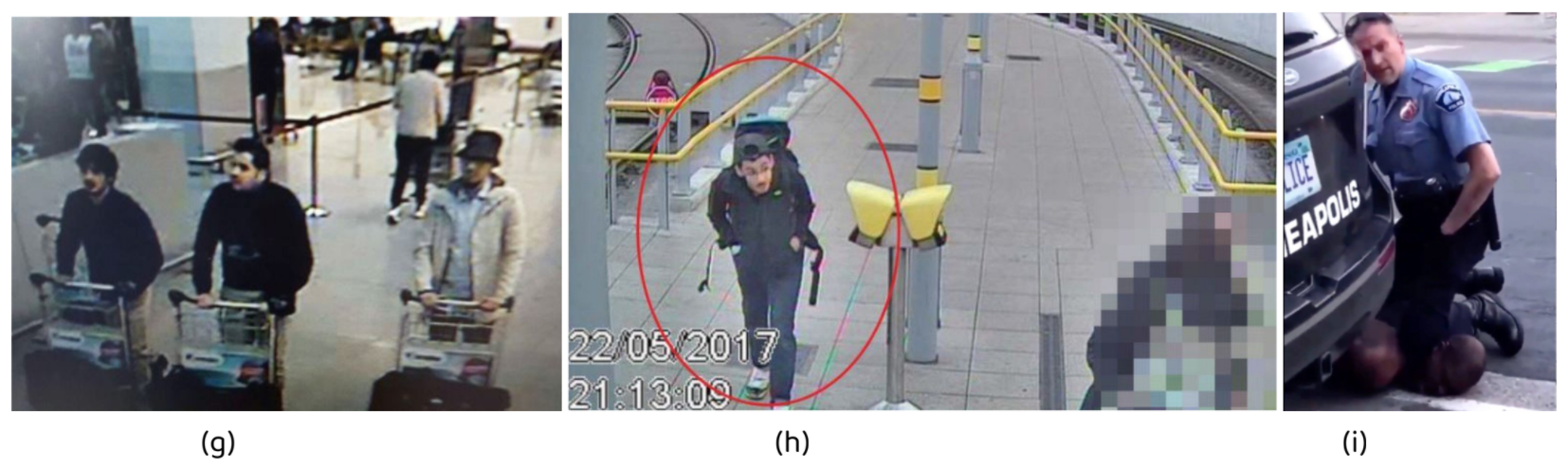

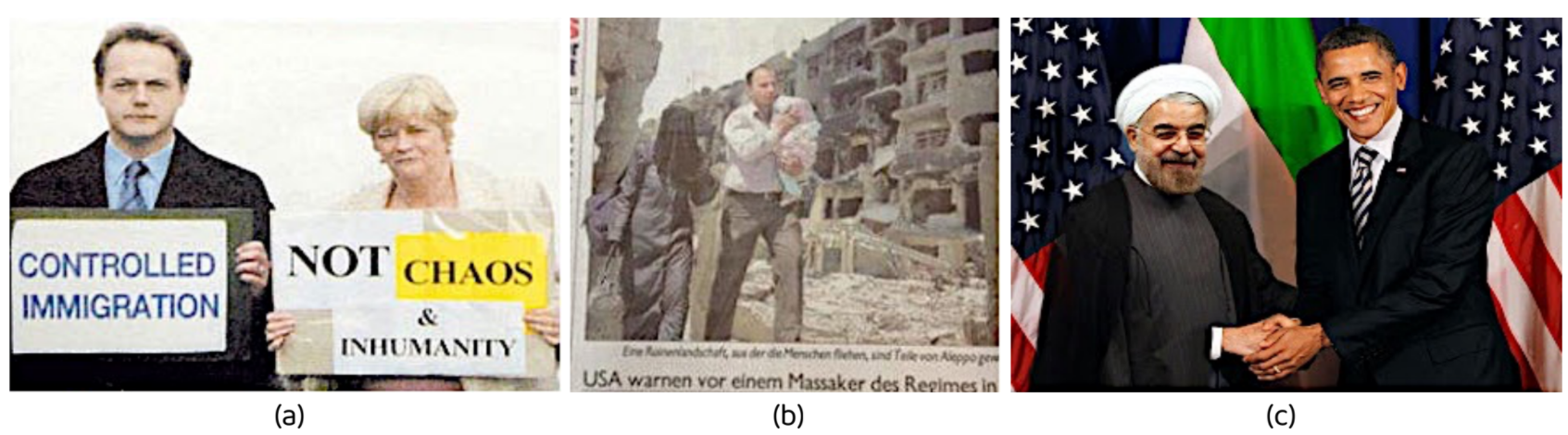

Today, we live in a ‘if–there–isn’t–a–picture–of–something–it–didn’t–happen’ sort of world, and in this era, acceptance of photographs (like the ones presented in Figure 2) as proof comes as naturally to us as breathing.

Figure 2 (a) April 2005: British politicians Ed Matts and Ann Widdecombe holding a pair of signs that together read "controlled immigration – not chaos and inhumanity". (b) July 2012: A family fleeing a bombed-out neighborhood in war-torn Aleppo, Syria. (c) July 2015: US President Barack Obama shaking hands with Iranian President Hassan Rouhani amidst Iran nuclear deal. [Pictures courtesy of Fourandsix Technologies Inc.]

Figure 2 (a) April 2005: British politicians Ed Matts and Ann Widdecombe holding a pair of signs that together read "controlled immigration – not chaos and inhumanity". (b) July 2012: A family fleeing a bombed-out neighborhood in war-torn Aleppo, Syria. (c) July 2015: US President Barack Obama shaking hands with Iranian President Hassan Rouhani amidst Iran nuclear deal. [Pictures courtesy of Fourandsix Technologies Inc.]

What’s interesting about these photographs is that they each carry within themselves enough information to help us form an opinion about the reality of the situation being depicted in the scene at that exact moment in time. And it is this information carrying capacity of visual data that leads us to recognize it as not only self–sufficient but also self–evident.

Want to learn more about photographic evidence? Check out the full course here:

Failings of Digital Images

Digital images have an incontrovertible influence on our perception of reality, but as compelling as they are, the picture they paint may not always be accurate. Digital images are inherently susceptible to tampering, and the possibility of manipulation is especially worrisome in scenarios where this digital content is being treated as evidence for making decisions and judgments with serious repercussions.

Consider for instance, the pictures we saw earlier in Figure 2, all of which were informative and influential, but none of which were the truth. Figure 3 presents the original versions of those pictures.

Figure 3 (a) Original version of the picture in Figure 2(a) showing Matts and Widdecombe campaigning for a Malawian family of asylum seekers to be allowed to stay in Britain. (b) Original version of the picture in Figure 2(b) showing no visible bomb damage within the scene. (c) Original version of the picture in Figure 2(c) showing Obama meeting Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh in 2011. [Pictures courtesy of Fourandsix Technologies Inc.]

Figure 3 (a) Original version of the picture in Figure 2(a) showing Matts and Widdecombe campaigning for a Malawian family of asylum seekers to be allowed to stay in Britain. (b) Original version of the picture in Figure 2(b) showing no visible bomb damage within the scene. (c) Original version of the picture in Figure 2(c) showing Obama meeting Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh in 2011. [Pictures courtesy of Fourandsix Technologies Inc.]

By simply changing a few details in a photograph, one can effectively alter the entire reality it depicts, thereby affording such data a tremendous capacity for deception. And though it may seem like a recent trend, instances of photo tampering can be traced back to as early as 1860, i.e., within half a century of the invention of photography itself!

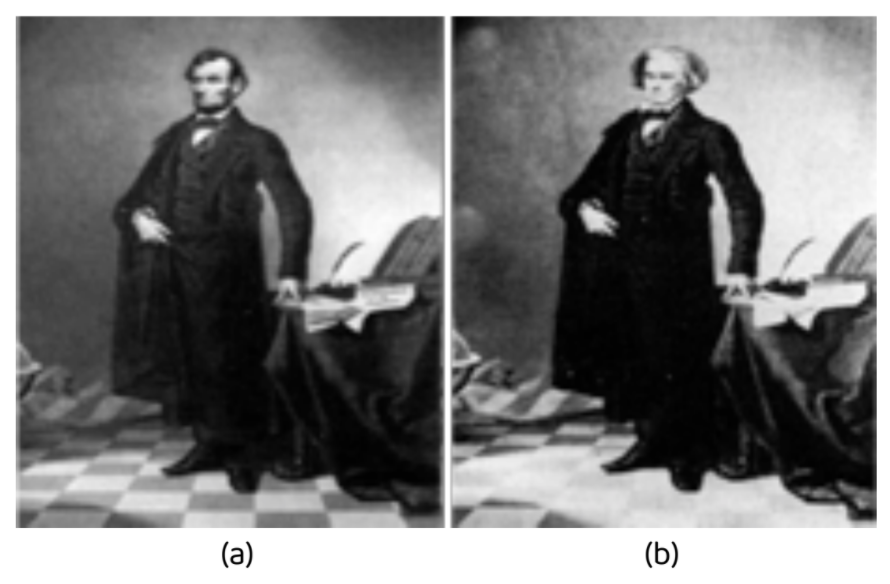

Figure 4 One of the earliest examples of photo tampering in history. (a) The iconic portrait of Abraham Lincoln (c.1860) was found to be a composite of Lincoln’s head and South Carolina politician John Calhoun’s body (b). [Pictures courtesy of Fourandsix Technologies Inc.]

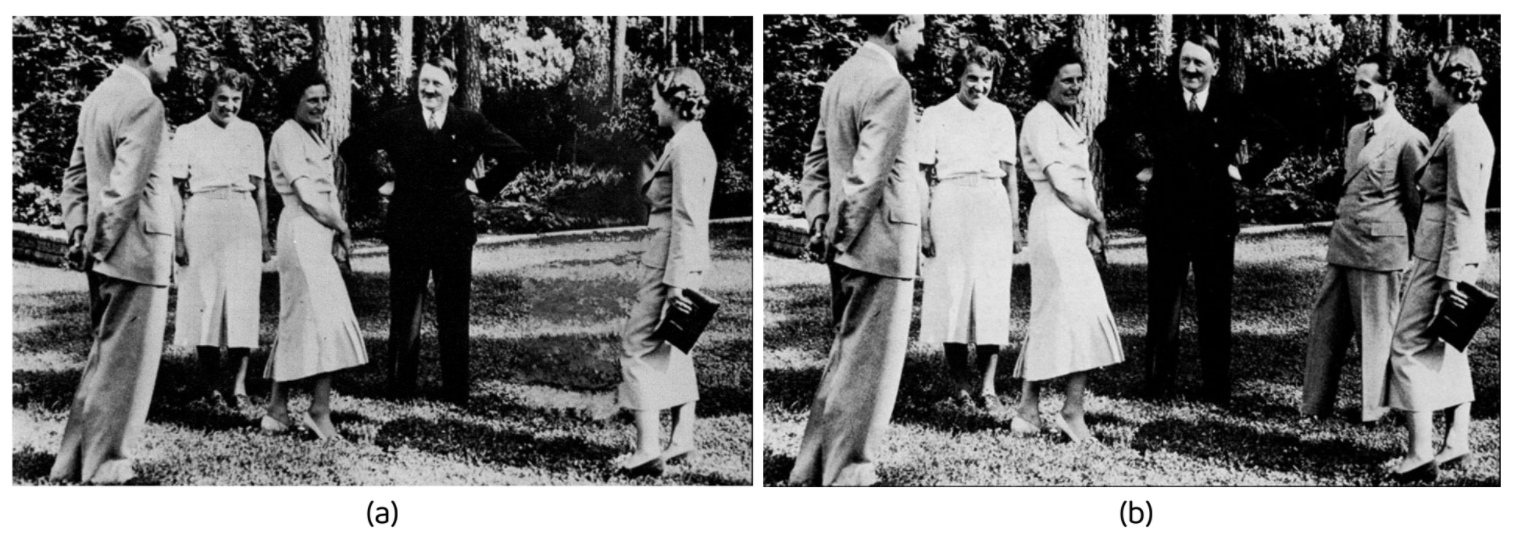

Figure 5 In this doctored photograph (a) (c.1937), Joseph Goebbels (second from the right) was removed from the original photograph (b) after Goebbels fell out of favor with Hitler. [Pictures courtesy of Fourandsix Technologies Inc.]

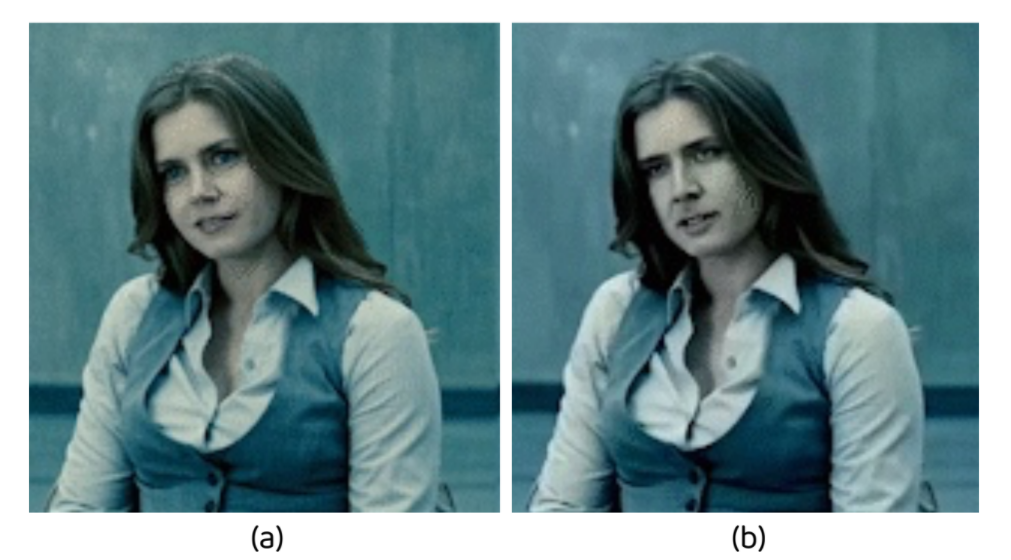

In the pre–digital era — when photos were recorded on film — tampering could only be performed by skilled photographers in specialized photo labs. In the post–Photoshop world however, the widespread availability of inexpensive yet sophisticated image editing software has made content manipulation so easy that even novice individuals with minimal skills can create plausible and convincing forgeries. And now that we have entered the deepfake [4] era, there’s no shortage of simple software and apps like FakeApp and DeepFaceLab that have the ability to create some of the most realistic forgeries ever to exist (Figure 6).

Figure 6 (a) Amy Adams as Lois Lane in the film Man of Steel. (b) Nicholas Cage as Lane, courtesy of deepfake technology. [Pictures Courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures and Nick Cage DeepFakes]

As we have seen, while a picture may be worth a thousand words, those words may not necessarily be true.

A Look at the Social Impact of Image Manipulation

Photographs have long been perceived as distinctively impartial and infallible eyewitnesses, and the visual evidence they proffer is continually used for post–event analysis and decision–making in several sensitive areas such as politics, journalism, civil and criminal investigations and litigations, surveillance, and military and intelligence operations. In all these areas, photographs are regarded as an especially privileged source of information. They seem almost to compel belief, and this power of persuasion stems both from their capacity to convey verisimilitude and the mechanical quality of their assertion to objectivity.

We have an innate tendency to believe what we see, and this tendency renders us susceptible to deception. Following are a few real-world examples of image manipulation with real-world consequences.

Figure 7 Missouri University professor R. Michael Roberts and co-authors retracted their paper (Cdx2 Gene Expression and Trophectoderm Lineage Specification in Mouse Embryos) published in Science after an investigation revealed that accompanying images were doctored. Contrary to conventional wisdom, the published research presented evidence that the first two cells of mouse embryos possess markers that indicate from a very early stage whether they will grow into a foetus or placenta. An investigating university committee found that lead author and post-doctoral researcher Kaushik Deb deliberately altered images of the embryos. Deb abruptly resigned his position and moved with no forwarding address or explanation. The committee said Roberts was cleared of wrongdoing by the committee, but that there was some concern over "whether he had acted appropriately at all times" during the research period. "Since he addressed that in the letter he sent to Science, we had no reason to suspect anything other than that he had been tricked." [Picture Courtesy of Fourandsix Technologies Inc.]

Figure 8 In July 2010, Malaysian politician Jeffrey Wong Su En produced a doctored photo of himself being knighted by the Queen of England (a). Responding to these claims of knighthood, a spokesperson from the British High Commission said, "We can confirm that we have no record of any honor having been conferred at any time by the British Government on Jeffrey Wong Su En". Wong was in fact, inserted into a photo of Ross Brawn receiving the OBE from the Queen (b). [Pictures Courtesy of Fourandsix Technologies Inc.]

Figure 9 Photographer Terje Hellesö won the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency's Nature Photographer of the Year award for his stunning photos of endangered animals. Several of Hellesö's photographs of the lynx, however, were digitally created by compositing stock photos into nature scenes. This manipulation was first detected in September 2011 by environmentalist Gunnar Gloerson, when he noticed that one of Hellesö's photos, which was taken in the month of July, showed a lynx in winter fur. [Pictures Courtesy of Fourandsix Technologies Inc.]

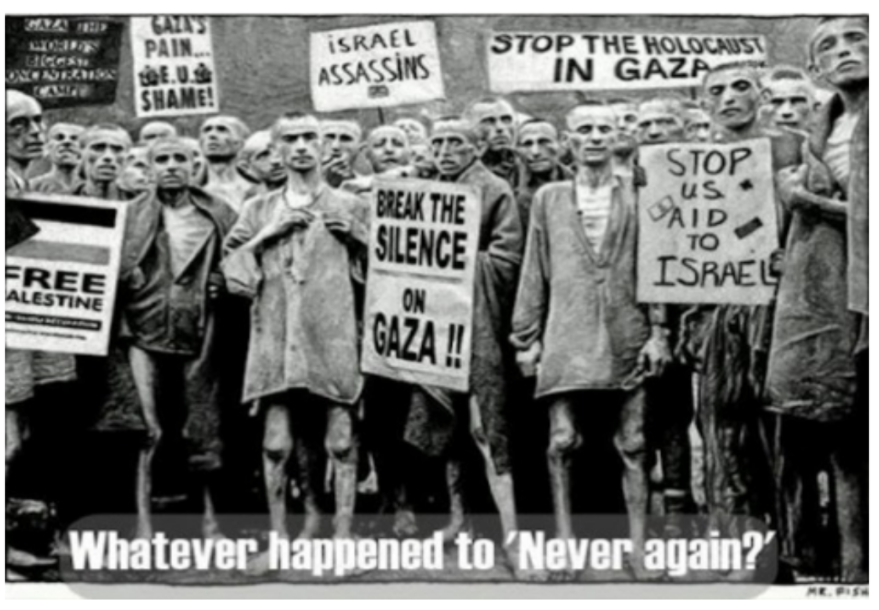

Figure 10 In November 2014, a pro-Palestinian Facebook group posted a doctored photograph of emaciated inmates of Nazi concentration camp holding photoshopped signs with messages that admonished Israel and demonstrated support for Palestinians in Gaza. [Picture Courtesy of Fourandsix Technologies Inc.]

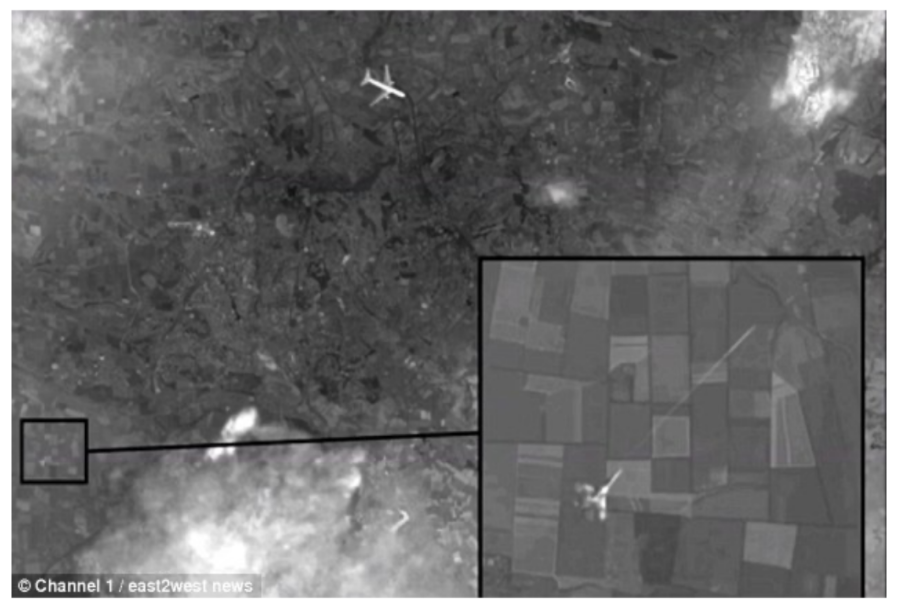

Figure 11 After months of denying any involvement in the downing of Malaysian Air’s flight MH17 over Ukraine, Russian state media ran a story in November 2014, calling attention to allegedly new satellite imagery it claimed proved that MH17 (top of the picture) was shot down by a Ukrainian fighter jet (bottom left). However, it didn’t take much time for experts to determine that the photo was a composite of Google Earth imagery from 2012, stock photo of a Boeing jet, and a section from Yandex maps. It was also affirmed that the location of the plane shown in the photo did not exactly correspond to the actual path that MH17 took. [Picture Courtesy of Fourandsix Technologies Inc.]

Figure 12 (a) Covering a solidarity march through Paris by world leaders after the Charlie Hebdo terrorist attacks in January 2015, Israeli ultra-Orthodox Jewish newspaper HaMevaser published a picture of the march in which prominent female world leaders had been removed from the original photo (b). Orthodox Jewish publications have a policy against printing photos of women, but this picture attracted special condemnation for virtually erasing important and influential women from the world stage. [Pictures Courtesy of Fourandsix Technologies Inc.]

While the credibility of digital images may have taken a significant hit over the past years, their evidentiary utility remains undeniable. As the court in a Georgia case [5] rightly said:

We cannot conceive of a more impartial and truthful witness than the sun, as its light stamps and seals the similitude of the object on the photograph put before the jury; it would be more accurate than the memory of witnesses, and as the object of all evidence is to show the truth, why should not this dumb witness show it?

To Err on the Side of Caution

Photographs are an unquestionably powerful source of information, both inside and outside the justice system. They tell us about the state of the world by presenting a picture that is as informative as it is compelling. However, what we have seen so far is but a glimpse of the threat tampered evidence poses in our world today.

Benjamin Madison III makes the following caution in his law review paper titled ‘Seeing Can Be Deceiving: Photographic Evidence In a Visual Age – How Much Weight Does It Deserve?’;

…… Impressed by advances in photography, courts generally favour photographic evidence, often according it substantial weight.Although photographic evidence is an asset to the adept trial lawyer, neither courts nor lawyers fully understand the capacity of photographic evidence for deception or improper influence.

That being said, we — all of us — need to learn to be more aware and mindful of the content that we have become so accustomed to consume in our everyday lives. As Bertrand Russell once said, “In all affairs it's a healthy thing now and then to hang a question mark on the things you have long taken for granted.”

As we embark upon the journey of this course, we will learn how to resolve some of those question marks.

This is just an intro! If you want to learn more, enroll in our 20-hour online workshop:

1 United States courts admitted photographic evidence as early as 1860. See Luco v. United States, 64 U.S. (23 How.) 515, 541 (1860).

2 The Amateur Photographer once published an item describing how a man was proved innocent of a crime by just a casual photograph. The accused and the deceased were known to have quarreled. Later the two went sailing in the harbor of Rio de Janeiro in a small boat. The accused returned with the body of the deceased and firmly asserted that he had met his death accidentally by falling from the masthead to the deck. Unfortunately for the accused, an oar was missing and doctors testified that an oar could have been the weapon used. Things looked bleak until a passenger on a steamer made public some startling evidence. He had happened to snap a picture of the harbor with a little box camera, and when several days later he had developed it, he had noticed a dark spot upon the sail of one of the small craft included in the view. Upon enlargement, the craft was shown to be the boat owned by the deceased, and the spot proved to be the image of a man falling from the mast, thus aiding in proving the accused's innocence!

3 In 1936, Léon Blum, the French statesman, was assaulted in a pre-election riot, and his antagonists were convicted largely on the evidence of a newsreel photographer who had been taking pictures of the disturbance from the roof of a building a block away. He used a telephoto lens and the faces of the trio were shown clearly.

4 We will discuss deepfakes in detail in Module 4 of this course, which goes into photographic evidence analysis in depth.

5 Franklin v. State, 69 Ga. 42, 49 Am. Rep. 748.

References and Further Readings

- Robert Hirsch (2000). Seizing the Light: A History of Photography, McGraw Hill.

- John Hannavy (2008). Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography, Taylor and Francis.

- Charles Calvin Scott (1938). Photography in Criminal Investigations, Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, Vol. 29, Issue 3.

- Jens Jaeger (2005). Police and Forensic Photography, The Oxford Companion to the Photograph, Oxford University Press.

- Benjamin V. Madison III. Seeing Can Be Deceiving: Photographic Evidence in a Visual Age - How Much Weight Does it Deserve?, William & Mary Law Review, Vol 25, Issue 4.

- D. Smith (1994). The Sleep of Reason: The James Bulger Case, Century Arrow Books.

- (2006) Report into the London Terrorist Attacks on 7 July 2005 (PDF), Intelligence and Security Committee, BBC News.

- (2009) 3 witnesses identify Kasab, court takes on record CCTV footage, The Economic Times.

- Christopher Bucktin (2013). Boston bomber caught on CCTV: FBI close in on suspect seen dropping bag in street, Mirror.

- Joseph Goldstein and Marc Santora (2014). Staten Island Man Dies From Chokehold During Arrest, Autopsy Finds, The New York Times.

- Ashley Southall (2019). Daniel Pantaleo, N.Y.P.D. Officer Who Held Eric Garner in Chokehold, Is Fired, The New York Times.

- (2016) What Happened at Each Location in the Brussels Attacks, New York Times.

- Connor Sephton (2017). What we know so far about concert atrocity, Sky News.

- (2020) Manchester Arena bomber Salman Abedi captured on CCTV seconds before blast, BBC News.

- Evan Hill, Ainara Tiefenthäler, Christiaan Triebert, Drew Jordan, Haley Willis and Robin Stein (2020), How George Floyd Was Killed in Police Custody, The New York Times.

- Meredith Deliso (2021) Timeline: The impact of George Floyd's death in Minneapolis and beyond, ABC News.

- Alia Chughtai, Know Their Names, Al Jazeera, https://interactive.aljazeera.com/aje/2020/know-their-names/index.html.

- Witness Media Lab, Prepare, Don't Panic: Synthetic Media and Deepfakes.

- John Brandon (2018). Terrifying high-tech porn: Creepy 'deepfake' videos are on the rise. Fox News.

- Oscar Schwartz (2018). You thought fake news was bad? Deep fakes are where truth goes to die, The Guardian.

- Raahat Devender Singh (2018). The Rise and Rise of Fake Videos, Medium.

- Sven Charleer (2019). Family fun with deepfakes. Or how I got my wife onto the Tonight Show, Medium.

- J. Kietzmann, L.W. Lee, I.P. McCarthy, T.C. Kietzmann (2020). Deepfakes: Trick or treat?, Business Horizons. Vol. 63, Issue 2, pp.135–146.

Author

Latest Articles

BlogApril 7, 2022Detecting Fake Images via Noise Analysis | Forensics Tutorial [FREE COURSE CONTENT]

BlogApril 7, 2022Detecting Fake Images via Noise Analysis | Forensics Tutorial [FREE COURSE CONTENT] BlogMarch 2, 2022Windows File System | Windows Forensics Tutorial [FREE COURSE CONTENT]

BlogMarch 2, 2022Windows File System | Windows Forensics Tutorial [FREE COURSE CONTENT] BlogAugust 17, 2021PowerShell in forensics - suitable cases [FREE COURSE CONTENT]

BlogAugust 17, 2021PowerShell in forensics - suitable cases [FREE COURSE CONTENT] OpenMay 20, 2021Photographic Evidence and Photographic Evidence Tampering

OpenMay 20, 2021Photographic Evidence and Photographic Evidence Tampering

Subscribe

Login

0 Comments